Cultural Restitution

SHARE ARTICLE

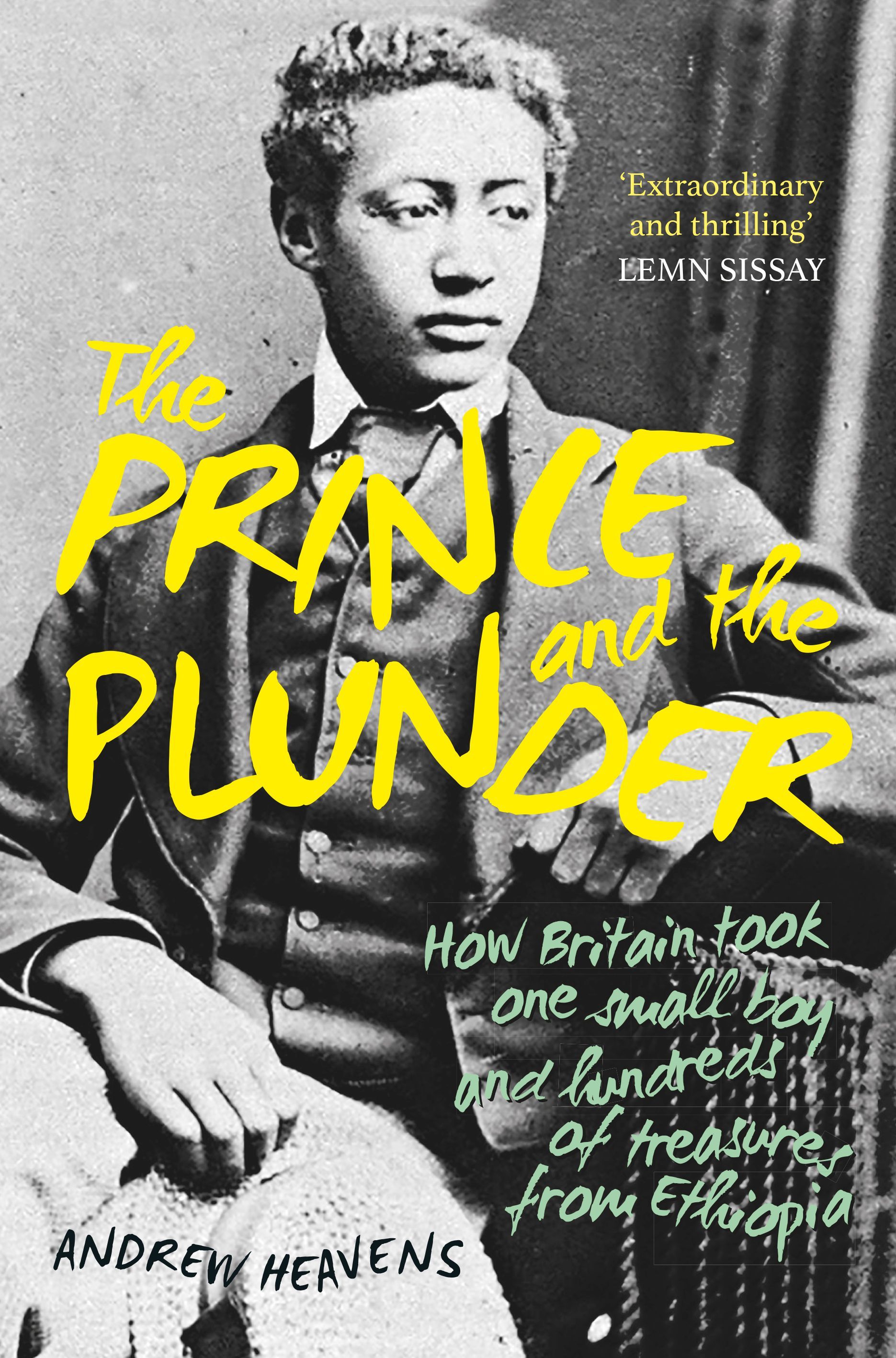

If the story of the Abyssinian Emperor Tewodros II is considered a little-known episode in British imperial history, then the story of his son Alamayu merits little more than a footnote. But a new book by Andrew Heavens, The Prince and the Plunder, is about to change all that.

Let’s remind ourselves of the events that took place in Abyssinia in 1868. A British expeditionary force sent to recover hostages from Emperor Tewodros’ mountain fortress at Maqdala, defeated the Emperor’s army and ended with Tewodros taking his own life. The future of Tewodros’ son, the 7-year-old prince Alamayu, became the responsibility of the leader of the British expedition, Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Napier. En route to a transport ship headed for England, Alemayu then suffered the loss of his mother, Queen Tirunesh, who died of a disease of the lungs, probably tuberculosis.

Without father or mother, a separated and traumatised young boy watched his homeland disappear over the horizon from the deck of an Indian steamship. He would never see his homeland again.

On arriving in England, he became something of a colonial celebrity, with Queen Victoria taking a special interest in his welfare and leading photographers falling over themselves to take his portrait. However, despite this celebrity status, all was not too well under the surface: dark moods and a lack of direction; unhappy years within an unforgiving Victorian school system; a mishmash of tutors and guardians; and an unsuccessful spell at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. Alamayu would die aged 18, eleven years after arriving in England, from a cause nobody could quite agree on. Pneumonia or perhaps another victim of tuberculosis.

It’s clear from this all too short life that Alamayu never fulfilled his royal destiny or achieved the full potential that might have been. His own impressions of a short life in Victorian England were never consigned to paper; his voice remains almost completely silent. As a result, narratives have over-relied on crafted impressions, consigned to letters and memoirs by those who met or thought they knew the young prince.

But they often conflict. Take, for instance, these two conflicting impressions, just two of many relayed by Heavens to illustrate the problem of reaching inside Alamayu’s state of mind. Writing to the Treasury in 1872, the Rev. Thomas William Jex-Blake, one of several of the young prince’s government-appointed guardians, reported on his “considerable social tact, and instinctive good breeding”. He described Alamayu “in excellent health and spirits, and enjoying life thoroughly”. But four years later, we learn of a boy out of his depth and seriously in despair. Writing in her diary, the artist Dorothy Tennant believed “the boy is depressed and unhappy”.

In his attempt to untangle the truth behind Alamayu’s silence, Heavens has produced an exceptionally fascinating, evenly balanced and moving account of Alamayu’s life. While there are scores of books recounting the story of Tewodros and the events at Maqdala, there are precious few biographies of this young prince… and none of them more rewarding to read than this one.

Heavens set out to follow the evidence. But it's a sticky path that takes the reader on a journey through multiple, contradictory accounts, missing official records and what Heavens calls ‘walls of establishment silence’. As a result, and despite heroic efforts, we can't be entirely sure we'll ever know what Alamayu thought about his stay in England, or whether he still held out hope for a return to his homeland. So, despite all the new information that Heavens has juggled to throw light on the young prince’s life in England, Alamayu's voice remains silent.

However, this is a book of two halves and there's another reason why it delivers value to our knowledge of this little-known Abyssinian campaign. Heavens devotes the second part of this book to identifying the whereabouts of plunder removed by Napier’s forces now in storage or sometimes on display in public, military, church and private collections. These comprehensive lists, comprising at least 830 of known looted objects, include those he's identified in present collections, objects already returned to Ethiopia, as well as objects still missing. Heavens continues to update these lists for historians and biographers and further details are available at www.theprinceandtheplunder.com. They represent an invaluable resource for the Ethiopian government's attempts to recover the loot plundered from Maqdala.

Speaking recently at a launch of The Prince and the Plunder, Heavens insisted “It’s not a campaigning book. I’ve used the objects to tell the story. It’s a way of saying even though we’ve forgotten the story, if we look around us it’s everywhere”.

And what of the young Prince himself? Queen Victoria wanted his funeral to be held at St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle. She also asked that personal trinkets she’d given him were to be buried in his labelled coffin. This coffin still lies in catacombs outside St George’s Chapel.

There have been numerous requests from church and state to repatriate Alamayu’s remains to Ethiopia, including a direct appeal made to the late Queen Elizabeth II in 2007 by the then President of Ethiopia. But the reply is always the same: the coffin lies alongside forty others, they couldn’t move it without disturbing these other remains. This, Heavens points out, is "an odd, shifting position" as other remains have been moved, most recently those of Princess Alice of Battenberg whose remains were transferred to the Russian Orthodox Church in Jerusalem in 1988. With the arrival of a new monarch, exceptionally well-versed in world religions, there are some who hope for a change in policy. St George's Chapel is after all a Royal Peculiar, which means it falls under the direct jurisdiction of the monarch.

In the meantime, that is where Alamayu will continue to rest. A foreign prince buried in a foreign land. “So much had gone unsaid through his life; so few had spoken out for him,” writes Heavens. “And his death when it came was abrupt and absurd”. It's the objects remaining that help tell his story.

The Prince and the Plunder by Andrew Heavens. Published by The History Press, Feb 2023

Photo: Detail of a portrait of Prince Alamayu by Julia Margaret Cameron, 1868

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

More News