Cultural Restitution

SHARE ARTICLE

Among the vast cache of leaked papers published this week by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) lies evidence of the extraordinary lengths taken by antiquities dealer Douglas J Latchford to conceal items he acquired during decades of looting and trafficking in Cambodian artefacts.

Previously undisclosed documents reveal that Latchford and his family controlled secret trusts in offshore tax havens. According to Latchford’s family, these were set up for tax and estate planning purposes. But an extensive report published in The Washington Post suggests the first of two Jersey-domiciled trusts controlled by Latchford and his family was set up in June 2011 - just three months after U.S. authorities began investigating his links to looted artefacts.

Offshore companies and trusts based in tax havens can provide a high degree of protection from prosecutors seeking to recover assets.

Named after the Hindu god Skanda, the Skanda Trust held substantial financial assets, as well as a London property and Latchford’s collection of antiquities, including scores of bronzes and other religious figures worth millions of pounds. At a later date, the family’s assets in Skanda Trust were transferred into another Jersey-based trust named after the Hindu god Siva.

Unravelling and repatriating any looted objects that may lie sheltered within these trusts will be complicated as the trustee for both entities is a British Virgin Islands-registered ‘private trust company’ – another layer of protection added by Latchford.

For many years Douglas Latchford, a dual citizen of Thailand and the UK, enjoyed a reputation as a prominent dealer and collector in Southeast Asian art and antiquities. His obsession for collecting Khmer treasures, mostly Hindu and Buddhist sculptures, began in the 1970s. For the next forty years he sold, donated or brokered Khmer objects to leading collectors and museums around the world. He was also a major supplier of Cambodian merchandise for auction houses and dealers, including the British dealer Spink & Son. As the author of three books on Khmer antiquities, he was often called upon to identify and authenticate Khmer works of art.

However, these activities masked a very different pattern of fraud and illicit art trafficking. Latchford was a key player in the systematic looting of ancient Cambodian antiquities, sourcing legitimate treasures from unauthorised excavations, looters and smuggling networks. During the period from the mid-1960s to the 1990s when Cambodia was blighted by civil war and the genocide of the Khmer Rouge regime, the country’s temple complexes suffered from widespread, organised looting. Artefacts could be picked up by looters and smugglers for a fraction of their value in the West and Latchford, according to prosecutors, was at the heart of this illicit trade.

To conceal the true origins of his merchandise, he misrepresented the provenance of objects that he sold, falsifying their invoices and shipping documents. The books he wrote were used to legitimise looted objects, before selling them on to major collectors.

Investigations into Latchford’s trading activities continued for eight years before he was finally indicted by the U.S. Justice Department in November 2019. Prosecutors demanded the return of “any and all property” derived from his illicit trafficking, including all financial proceeds from his sales. But before standing trial and before his assets could be traced, Latchford died.

His daughter, Julia Latchford, who is a beneficiary of the Jersey trusts along with her husband Simon Copleston, announced in January this year that she would repatriate 125 antiquities to Cambodia, a collection valued at around $50 million. This donation doesn’t draw on any of the Latchford-linked objects now in public or private collections. Described as the biggest repatriation of relics in the region’s history, a New York Times article announced the gift “honours, if not absolves her father”.

However, this week’s leaked papers tell a different story. They appear to confirm that Latchford had proposed this donation in 2018 to the U.S. ambassador in Cambodia in return for helping him and his family gain protection from criminal prosecution.

In a statement to the ICIJ, Julia Latchford’s attorneys explained she was only made aware of her father’s illegal activities after his death. She also maintains the Jersey trusts “included multiple family assets”; they were not set up to conceal the origin of Latchford’s collection nor the proceeds from his sales. According to her statement, the private trust company “was not designed to obscure the trust structure or what it held, nor to increase secrecy in any way”.

Latchford’s daughter and her husband are not being accused of any wrongdoing. Nevertheless, the disclosure of these two Jersey trusts raises questions about the legitimacy of all objects traded or still held within Latchford’s collection and, in particular, over the provenance of Latchford-linked Khmer objects now held in public collections around the world.

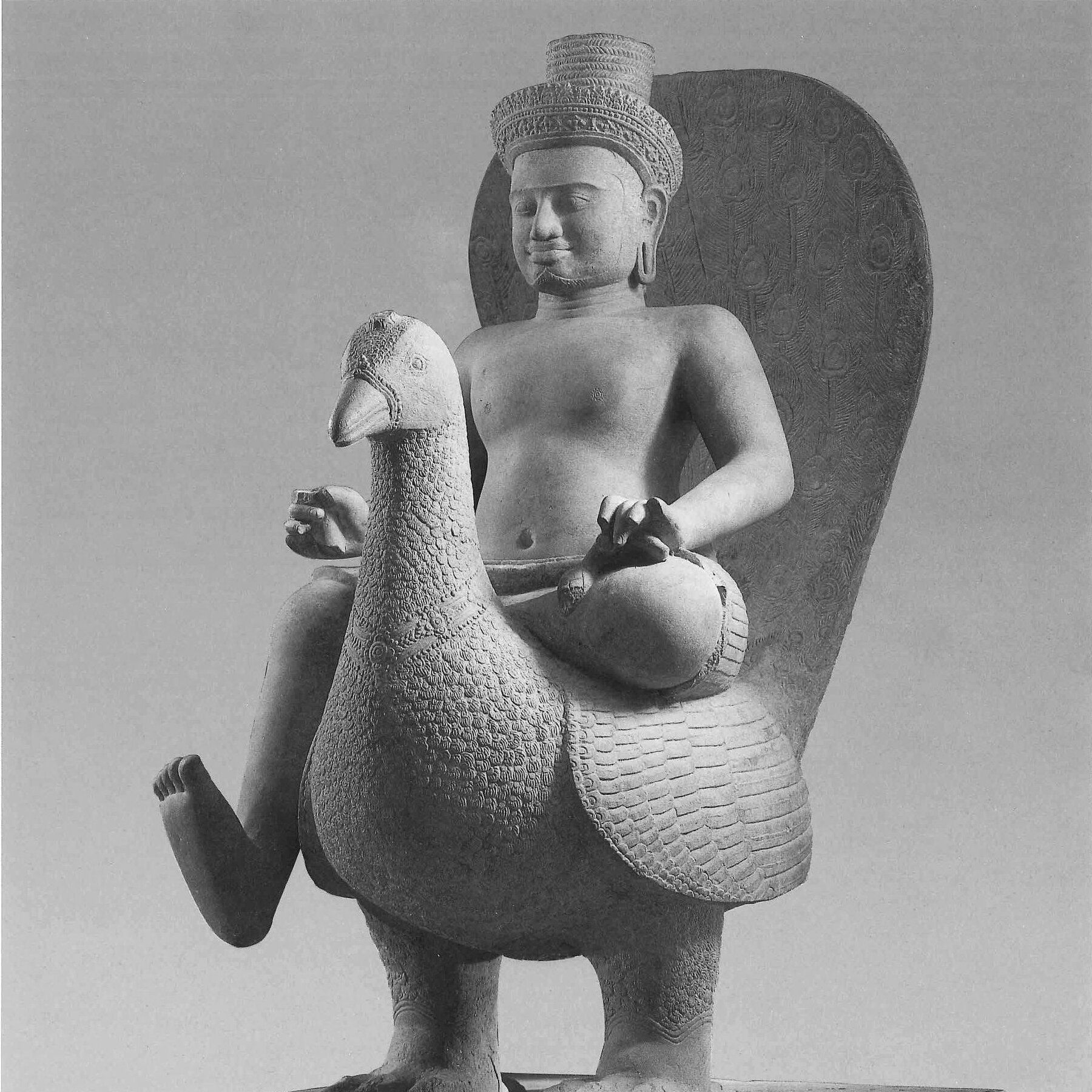

'Skanda and a Peacock', Cambodia, 10th century. Courtesy of Offices of the United States Attorneys

U.S. investigators are continuing to pursue the repatriation of looted objects from Latchford’s collection and several museums and collectors have already started repatriating artefacts to Cambodia. In July this year, a 10th century sandstone statue of Skanda astride a peacock, stolen from the Prasat Krachap temple in Cambodia around 1997, was recovered in New York. The statue had been acquired by Latchford from a broker on the border with Thailand. Latchford went on to sell this ‘Skanda on a Peacock’ to a corporate collection for $1.5 million, stating falsely that its country of origin was Thailand.

Meanwhile, The Washington Post reports that at least 27 Latchford-linked Khmer items still remain in prominent public collections. These include twelve objects in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, six in the Denver Art Museum, five in the British Museum, three in the Cleveland Museum of Art and one in the National Gallery of Australia. A further 16 artefacts were sold to museums by a Latchford associate, who prosecutors believe dealt in stolen artefacts. None of those museums approached by The Washington Post were able to provide documents confirming they'd been exported with the approval of Cambodia’s government.

Of course, the absence of export documentation or provenance information doesn’t prove that an object has been looted. But it does place a greater responsibility on the museum to research an object’s history. Where it can be proved an object has been removed illegally, there's a greater responsibility to return it to where it was stolen.

Asked about Latchford-linked objects in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a spokesperson said they were reviewing the indictment against him that references a Hari-Hara in their collection. But the spokesperson added: “It is unknown whether the Hari-Hara, a relatively common depiction of Vishnu and Shiva, are one and the same”. Meanwhile, the National Gallery of Australia said their object was now “the subject of a significant live investigation”. The Denver Art Museum said it is “in ongoing discussions with both U.S. and Cambodian governments” about its Latchford-linked items.

Every museum contacted reiterated that it takes provenance research very seriously; only the Los Angeles County Museum of Art declined to answer reporters’ questions about their Latchford-linked holdings.

Further revelations about trafficking antiquities and offshore trusts are expected in the months ahead. In the meantime, pressure continues to mount on museums holding Latchford-linked objects to investigate their places of origin. Opening Pandora’s box is likely to lead to many more surprises.

After this was written

Following these disclosures in the 'Pandora papers', the Denver Art Museum has agreed to return to Cambodia four artefacts, described of "extraordinary cultural significance", which were acquired by the Museum through Douglas Latchford.

Photo: Head of a Buddha (c. 920-50). Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. Gifted by Donald J Latchford

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

More News