Cultural Restitution

SHARE ARTICLE

Because Reverend John McLuckie, Associate Rector of St John the Evangelist, had visited Ethiopia as a student he was able to identify and grasp the true significance of a wooden plaque discovered in 2001 while clearing out the back of a cupboard in a Scottish Episcopal church in Edinburgh.

Since 1868 this holy ‘tabot’ had been stored away, forgotten and unrecognised in a distressed Victorian leather box.

A tabot is a consecrated, painted or carved plaque, made of wood or stone, which to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church is a representation of the Ark of the Covenant and the Ten Commandments. It represents the dwelling place of God on earth and is protected by a veil from public sight, only seen by priests. Removal from an Ethiopian church constitutes an act of sacrilege.

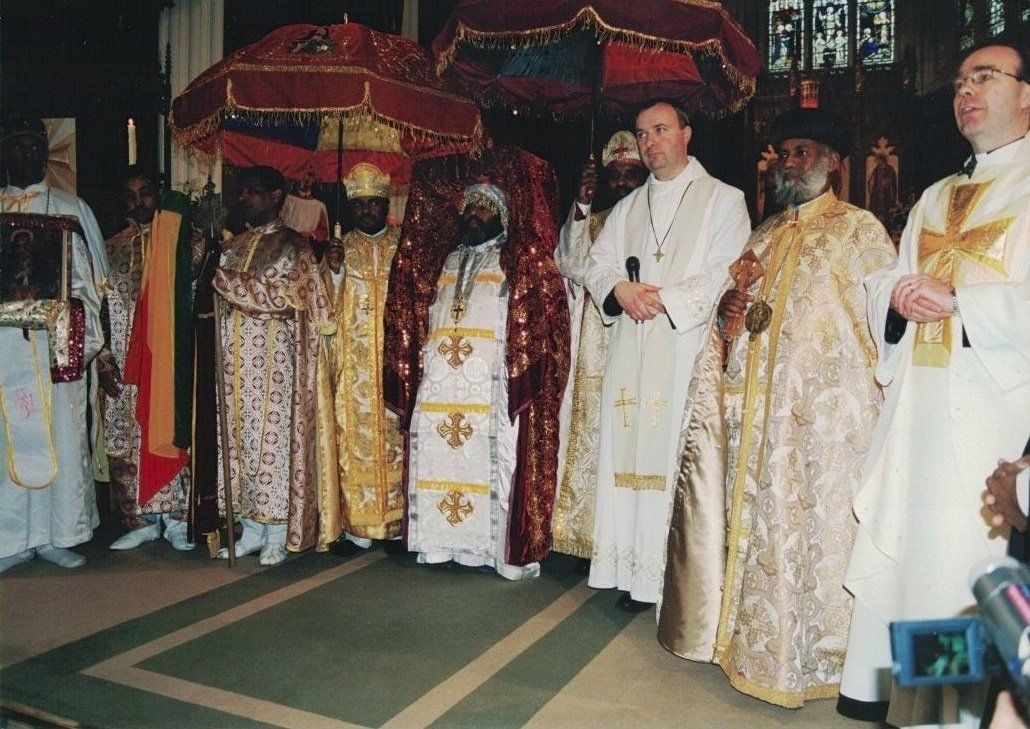

With no administrative protocols to frustrate its return and with an abundance of goodwill by St John’s towards the Ethiopian Orthodox church, a dialogue was opened and a handing over ceremony was organised within a few months of its discovery. Attending the ceremony, which took place at St John’s Episcopal Church on 27 January 2002, was a delegation from Ethiopia and London. The carved wooden tabot, thought to be over 400 years old, was ceremoniously carried through the church, wrapped up and covered by liturgical umbrellas, before being handed over to Archbishop Bitsu Abune Isaias and other representatives from the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

A national holiday was declared in Ethiopia and thousands of people lined the streets from the airport into Addis Ababa to welcome the return of the tabot to its home.

The tabot had been gifted to St John’s in 1868 by Captain William Arbuthnot (1838-1892), Aide de Camp and Military Secretary to General Robert Napier. Napier was the British Commander despatched in 1867 on a little known and less than glorious expedition to rescue a handful of Europeans (including the British Consul) held hostage for several years by the Abyssinian Emperor Tewodros II.

Following the crushing defeat of the Emperor’s army at his mountain stronghold of Maqdala on 13 April 1868, British troops proceeded to plunder the Emperor's mountain fortress of Maqdala and the nearby Christian church of Madhane Alam. Important sacred relics, tabots, crosses, items of royal regalia, illuminated manuscripts and other artefacts were seized by British troops in a frenzy of plundering. It is said that fifteen elephants and some two hundred mules were deployed to transport the plunder to a site where a hasty auction was held just a few days later. As was the practice for the period, the proceeds were shared among the troops as ‘prize money’ for a successful campaign.

Arbuthnot either looted this tabot directly from the church at Madhane Alam or acquired it bidding at this auction. Recognising the religious significance of the tabot, he gave it to St John’s directly on his return to Edinburgh.

Attempts to recover other looted tabots still held in the UK, including one in Westminster Abbey and eleven in the British Museum, have failed to meet with success.

Background to the Battle of Maqdala

For many years, the Ethiopian Government has lobbied for the return of hundreds of sacred, cultural and historical looted items now in British collections - royal and religious regalia, tabots (sacred plaques believed by Ethiopian Christians to symbolise the Ark of the Covenant), illuminated manuscripts and ‘human remains’ - seized by troops during a punitive expedition by the British to Abyssinia (modern day Ethiopia).

The episode is a little known and inglorious chapter in British imperial history, also one of its most ambitious and expensive campaigns.

In 1867, an overwhelming army of 13,000 British troops under General Sir Robert Napier was despatched from India to rescue a handful of Europeans (including the British Consul), held hostage for several years by the Abyssinian Emperor Tewodros II. The campaign involved an impressive logistical operation, including the construction of roads and a railway across 400 miles of mountainous terrain. It took over three months for Napier's expedition to reach Tewodros's mountain fortress at Maqdala (now known as Amba Mariam). The tragedy which then unfolded involved the crushing defeat on 13 April 1868 of the Emperor’s army and the suicide of the Emperor, who used a gun presented to him by Queen Victoria.

Widespread looting by soldiers at Maqdala and at the Christian church at Medhane Alem followed the battle. A clear act of sacrilege, this looting is largely ignored in military narratives about the campaign. Newspaper journalists who were present, including the Anglo-American journalist Henry M. Stanley, witnessed British soldiers tearing strips off the Emperor’s clothing and a soldier cutting locks of hair from the dead Emperor’s body.

Collecting trophies of war and their distribution as ‘prize money’ was common among armies during the colonial era. But the unedifying involvement of the British Museum's trustees by supporting the expedition with the aim of acquiring items for British national collections was described by its former Director, David Wilson, as ‘one of the less glorious episodes in the history of the Museum’. *

On the orders of General Napier, the British military authorities organised a two-day auction of plundered items just days after the looting had finished. It is said that fifteen elephants and nearly two hundred mules were deployed to transport the plunder to the site of the auction. The proceeds, totalling £5,000, were then shared among the troops, according to rank, as ‘prize money’ - a reward payment for a successful campaign.

Among those present throughout this auction was Richard (later Sir Richard) Holmes, an Assistant in the British Museum’s Manuscript Department who’d been appointed as ‘competent archaeologist’ to the expedition. Holmes aggressively bid and secured over 300 manuscripts on behalf of the Museum, as well as other royal artefacts removed from the Emperor’s treasury. He was later awarded both an

ex gratia payment by the Museum’s trustees and a campaign medal.

Even the British Prime Minister, William Gladstone, criticised the scale of this looting. Gladstone and Napier both felt the looted items should be held in Britain only until they could be returned safely to Ethiopia. Apparently, that time has never arrived.

Of the many hundreds of items known to have been seized following the battle, only a few have been returned to Ethiopia. The earliest restitutions include a

Kebra Nagast (Book of Kings), returned following a request from Emperor Yohannes in 1872 and a silver crown, presented to Ras Teferi in 1924 by King George V. Other returns have been made by private individuals. Meanwhile, about a dozen UK institutions plus several private collections hold many other major items of sacred, historic or cultural importance to Ethiopia, acquired through purchase, bequests or gifts following the auction. These institutions include the British Museum, British Library, Victoria & Albert Museum, Royal Library at Windsor Castle, Bodleian Library, Edinburgh University Library, John Rylands University Library, Manchester, Westminster Abbey and several regimental museums.

* David M Wilson, The British Museum: A History (British Museum Press, 2002), p. 173-4